An ingenious new treatment for schizophrenia

Cobenfy combines a novel mechanism of action with an ingenious design principle

Drugs for mental illness are notoriously hard. Human biology is complex, and the brain is even more complicated. We now have a good understanding of the basic mechanisms of neurotransmission, but the drugs we have for treating disorders like depression, anxiety and psychosis are often “spray and pray” approaches, either targeting the wrong mechanisms of dysfunction or targeting too many or too few. Antidepressants often stop working. Anti-anxiety medication can do little more than sedate. And many antipsychotic drugs have prohibitive side effects.

Nevertheless, there are rare cases when genuine breakthroughs occur in the field. Thorazine famously emptied out the cruel mental asylums of the 1950s and 1960s. L-DOPA provided genuine benefits for Parkinson’s patients. And there is no denying that the new generation of antidepressants works at least occasionally for a subset of patients. Last year one such potential breakthrough seemed to fly under the radar of breathless news dominated by politics and social issues. If its promise holds up, it could herald a new kind of treatment for schizophrenia.

As is well known, schizophrenia is a serious form of psychosis that is characterized by disordered thinking, hallucinations and impaired speech and expression. The disease profoundly impacts the quality of life of afflicted individuals, including being able to sustain social relationships and professional goals. In severe cases, as made infamous by the case of Michael Laudor, even high-functioning schizophrenics can become a fatal threat to themselves or others. Estimates of the prevalence of schizophrenia in the United States range from 0.25%-0.64%.

All drugs work by blocking or improving the function of proteins or receptors. Receptors in the brain include those that regulate the function of neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine. Neuropharmacological drug discovery starts with identifying these receptors and then discovering molecules that selectively inhibit or activate them. For instance, most antidepressants are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) which increase the concentration of serotonin by blocking its re-absorbption and improving a sense of well-being.

The “dopamine hypothesis” of schizophrenia, first developed in the 1960s, says that an excess of dopamine causes the symptoms of the disorder. To this end, existing drugs for schizophrenia target dopamine transmission by blocking two subtypes of dopamine receptors: D2 and D3. Unfortunately, these “first-generation” antipsychotics induce severe side effects including rigidity, tremors, weight gain and sedation. “Second-generation” antipsychotics which also target the norepinephrine receptor subtype, called 5-HT2A, are better tolerated but are also not free of muscle tremors, sedation and weight gain. Because of these side effects patients can stop taking the drugs. There has thus been a decades-long effort to discover new antipsychotic medicines with new mechanisms of action that retain the positive effects and minimize the negative effects. Progress has been slow and disappointing.

Cobenfy, approved in September 2024, is a breakthrough antipsychotic medication, the first drug with a completely different mechanism of action from existing schizophrenia drugs. Instead of targeting dopamine and serotonin receptors, Cobenfy targets receptors called the M1 and M2 muscarinic receptors, so named because they were originally discovered by their responses to the neurotransmitter muscarine. It is instructive to understand Cobenfy’s fascinating history to appreciate the discovery of its mechanism of action. The history also speaks to the rocky, serendipitous, uncertain road that often plagues the development of new drugs. In case of Cobenfy it also speaks to the ingenuity of drug hunters.

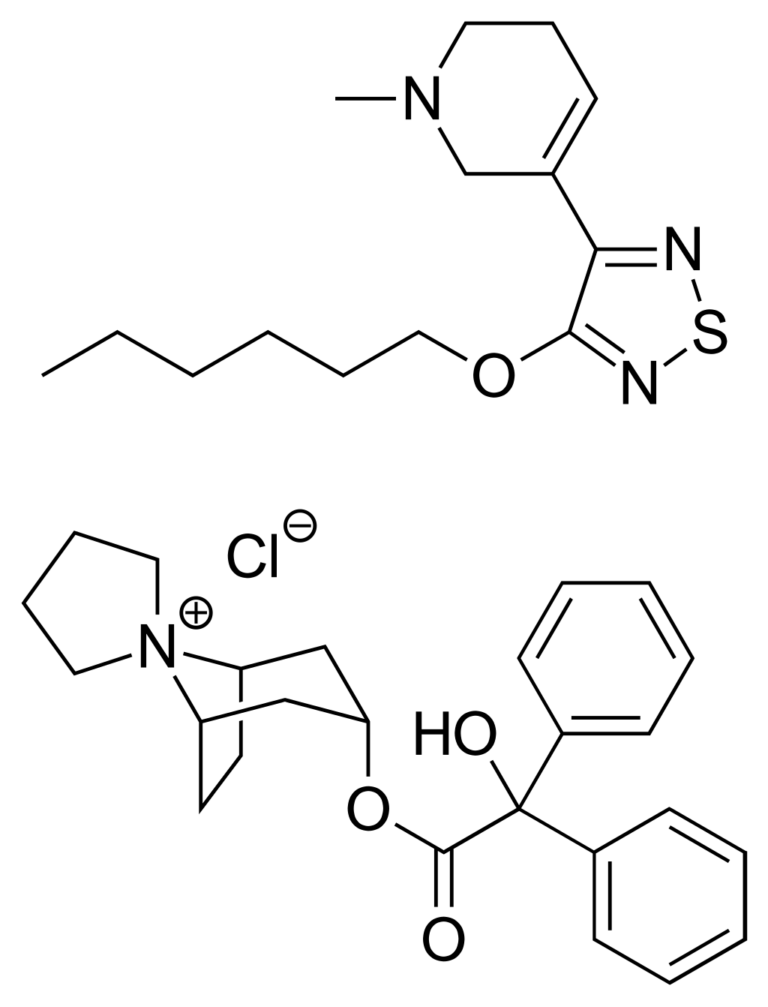

Cobenfy is a combination of two drugs – xanomeline and trospium chloride. Xanomeline is a muscarinic receptor agonist, which means it activates the muscarinic receptor. It was developed by Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk in the 1990s as a potential treatment not for schizophrenia but for Alzheimer’s disease – the M1 and M4 receptors had already been implicated in the etiology of the disease. While the drug did show some efficacy in slowing down cognitive decline, it also demonstrated serendipitous effects on managing psychosis symptoms. Unfortunately it was poorly tolerated, with severe side effects that included nausea, diarrhea and vomiting. These side effects were traced to its interactions with M1 and M4 receptors and led the drug to be abandoned. But – crucially for later studies – these receptors were not in the brain but were peripheral, expressed in the rest of the body.

Over time, M1 and M4 receptors were soon implicated in dopamine transmission. This led to a re-evaluation of xanomeline’s potential as an antipsychotic. In 2012, xanomeline was licensed to a company called Karuna Therapeutics which came up with the idea of co-formulating it with trospium chloride. Why trospium chloride? Because trospium chloride had already been marketed for a few years as a drug for overactive bladder. It also targets the muscarinic receptors, but it is a muscarinic receptor antagonist, which means it inactivates the receptors.

Karuna Therapeutics saw that there was a clever puzzle to be solved here: one drug is a muscarinic receptor agonist which acts in the brain and potentially mitigates the symptoms of schiphrenia, but its activation of these receptors in the rest of the body causes prohibitive side effects. Meanwhile another, completely unrelated drug, is a muscarinic receptor antagonist. But the most crucial aspect of trospium chloride is that it’s a charged molecule, and the basic laws of biochemistry say that charged molecules cannot readily cross the blood-brain barrier, an oily, tightly-knit membrane, that opens the gates to targeting the brain. Taken together, you now have a combination of a drug which targets the symptoms of schizophrenia and another drug which mitigates the adverse effects of that drug in the rest of the body because it cannot get to the brain. It’s an ingenious idea if you think about it.

In 2021, the combination which was called KarXT was evaluated in two clinical trials which measured the PANSS (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale) score tracking the ratio of beneficial to side effects in schizophrenia patients. In each case the participants reported a significant and meaningful change in the PANSS score relative to the placebo group. Most importantly, side effects were mild relative to other antipsychotic agents.

In March 2024, Karuna Therapeutics was wholly acquired by Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Cobenfy was approved by the FDA in September 2024. Its discovery will likely herald the advent of new drugs against this debilitating disease with a completely new mechanism of action that was found through a combination of serendipity and some very clever puzzle solving.

Very useful piece! Thanks much, Vijay